What went wrong with Hasan Ali in the T20 World Cup?

TV analysts and commentators will say it is a "slump in form of a quality bowler and Hasan will bounce back", but what technicalities led to the tiger claws losing its edge?

Picture a magician who is the coolest guy in the world to an eight-year-old, until his tricks eventually become mundane and he is no longer the dazzler he once was - until he has a new bag of tricks, and the cycle goes on.

This, in a way, is the story of Hasan Ali's international career so far.

About four months before the T20 World Cup in the United Arab Emirates, Hasan played in the second phase of the Pakistan Super League’s sixth edition, held in the same country.

As the leader of Islamabad United’s bowling den, Hasan led his coalition fairly well, taking 7 wickets at an average of 25.7 with a strike rate of 20.4 and an economy rate of 7.55, scalping best figures of 2/24 against Quetta Gladiators across 6 matches. Hasan was also the second-highest wicket-taker for his den in the Abu Dhabi route and overall the tenth highest, certainly leading his cubs in a manner expected from pride males, with his claws looking well sharp in time for the global spectacle.

Cricmetric gave Hasan the third-highest WPA score (Win Probability Added) of 0.654, with 0.390 composed of bowling and 0.264 of batting, only behind Rashid Khan and Hazratullah Zazai. Hasan’s Bowling WPA was the fifth-highest, behind Imran Khan Sr, Rashid, James Faulkner, and Shahnawaz Dahani.

With these strikes on the claws of the Mandi Bahauddin Lion and the reputation it has cultivated since emerging from the wilderness of a nearby village in Central Punjab, Pakistani fans were in the right to have high expectations of Hasan for this year’s T20 World Cup.

Those expectations were met in the form of 5 wickets at an average of 41.4 with a strike rate of 27.6 and an economy rate of 9.00 across 6 matches, best bowling figures of 2/44 against India in their opening match and a WPA of -0.306 (entirely composed of bowling), putting him all the way down on 196th in the WPA leaderboard. To begin shedding light beyond the surface level of how dismal this escapade was for the Mandi Bahauddin Lion, Hasan’s WPA—in contrast to other bowlers, was better than only Australia’s Mitchell Starc, Afghanistan’s Karim Janat, and Sri Lanka’s Lahiru Kumara.

The question rightly begs itself: What went wrong? How did Hasan’s claws lose their shine out of the blue? It is not as if Hasan experienced rapid aging in the 125 days between Islamabad United’s final fixture and Pakistan’s opening fixture against India and became a 38-year-old who could barely touch 130kph with the ball.

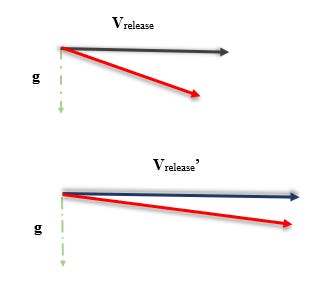

So what went wrong with Hasan? Shane Watson, T20’s ageless Morgan Freeman, says that having fluid control of the run-up speed enables a bowler to be able to bowl accurate lengths. Too much momentum in the run-up will equate to the ball pitching a bit fuller than intended; too little momentum shorter than wished for. If Watson were running in a bit slow, he would be pulling down a bit too hard by the time he got to the crease, resulting in a natural drag of the ball’s length (shorter than Watson wanted). Given this is true, it’s huge for bowlers: a one-meter change in length typically takes an eight-degree change in release angle on the sagittal plane, to achieve that without an equivalent change in release gives you a glut of options.

And it also makes intuitive sense. There exists a strong correlation of 0.58 between run-up speed and release velocity according to a Rene Ferdinands study, and many others have found that about 15-20% of release speed is determined by run-up velocity. So increased run-up speed would contribute to increased ball velocity and an increased ball velocity would translate to fuller-pitched darts given the same angle of release.

Angling the run-up for a specific type of batsman (LHB or RHB) may help yield better results. For instance, a right-handed pacer like Hasan himself may move his run-up a little bit wider for a RHB to be able to (without changing anything else) still run in a straight line, slightly alter his angle and run-up so he could actually get in closer to the stumps, going through the off stump of the batsman without really changing much at all.

For left-handed batsmen, right-handed pacers may move their run-up and mark a meter wider and run in from that angle straight through to the off stump of the LHB without changing anything in their action at all. The change of angle in their run-up generally aids them in changing the line bowled to a left-handed batsman without changing anything in their technique whatsoever.

I will be applying Watson’s theory (the cricketer, not the guy from your dreaded science textbooks) to explain how Hasan can improve his lengths, contrasting key exhibits from Hasan’s spell of 2/24 against the Gladiators and 2/44 against India.

Spells Analysis

Opening the bowling against a right-handed pace hitter, Hasan goes for the yorker, but ends up just missing it, resulting in an overpitched slower one that gives Usman Khan enough time to open up his arms and expansively drive the ball through point for four.

Too little momentum in the run-up and through the crease drags the ball shorter than intended. As a result, he is unable to land the yorker.

Owing to that, Usman was able to use his crease just before Hasan pitched the ball, which allowed him to open up his arms and expansively drive through point for four. Hasan’s front arm pull is loose, and his wrist position is also loose, also contributing to the failed attempted yorker.

(For context, Twitter analyst Flighted Leggie defines a missed yorker as “fuller than 1 meter and shorter than 3 m until 4.5 m”.)

In real-time, there appears to be little momentum in the run-up and through the crease, dragging the ball a bit shorter to bowl a 113.5kph attempted slower yorker about 4 meters short of the stumps that dipped in. Hasan’s run-up and gather also appear to be shortened for this delivery, not giving him enough time to complete his action.

It can be seen that Hasan was unable to deceive Azam with the slower one from the beginning. Azam made room for himself by moving a step away from his leg stump well before Hasan’s ball release to swat the freebie for four. Hasan’s front arm pull appeared to be weak. In slow-mo, Hasan’s wrist position appears to be not firm on this occasion, but loose, contributing to him being unable to successfully attempt the yorker. Hasan’s body position is a weak low-driven body position.

Here, Hasan opts for the “test match length”. Momentum in the run-up and through the crease are streamlined, so Hasan had full control of his length. Hasan even angled it in and cramped Pant for room. The problem? A negative matchup with a side of sheer brilliance from a generational talent.

Pant’s neutral position has a high backlift, which helps in generating power.

Just as the ball came within Pant’s reach, he began crouching down on his back knee and cleared his front leg, which gave him the freedom of doing anything he wanted, as it grants easy access to the ball; nor is there any hindrance to the bat swing. In the middle of Pant’s downswing, he lets go of his bottom hand, which generally powers the shot through, while the leading hand controls the shot. However, as a result of eschewing control of his bottom hand, Pant was able to extend his front arm fully and successfully whip the ball over the square leg boundary.

(Regarding the negative matchup, Watson explains that with Hasan coming around the wicket at the shorter side of Pant, which was only 18 meters long, Pant was comfortably able to essentially nullify the cramping Hasan created with the angle and successfully premeditate whipping the 135kph like cream cheese.)

Here, Hasan seems to have listened to what Watson talked about in the previous delivery and isn’t coming from around the wicket, but instead decided to bowl a 123kph slower slot delivery, which any decent hitter would eat for breakfast. In this case, Pant ate it one-handed again. However, this ball landed smack bang in the middle of the slot region, so one could theorize that Hasan was trying to bowl a similar length as the previous delivery but with pace off the ball so Pant could not have used it to his advantage again, albeit there was too much momentum for Hasan to have complete control of his length.

The ball was angling across Pant’s off stump, but because it was in the slot, Pant connected bat with ball and initiated the downswing well before it reached him, and also cleared his front leg again to lift the ball one-handed over the long-off boundary.

In this GIF, we can see that Hasan sprints 16 steps in a streamlined motion with momentum directed towards the batsman.

A 117kph back of a length delivery with width on offer.

Momentum through the run-up and crease is streamlined, so Hasan had full control of his length, and was able to bowl the back of a length.

How Can Hasan Ali Improve His Momentum/Length Accuracy From Here?

With this specific variable, there are a few external factors that Hasan would have to practice with (specifically mother nature).

For instance, Watson said he hated bowling down the breeze and downhill, as it creates a challenge in bowling your intended length going through the top of the stumps. Having a breeze against the bowler can cause the ball to slow down and swing a noticeable amount.

It can be countered with apt use of the wrist and taking a yard or two off the pace of the ball to get pushed by the wind.

As Harigovind points out in his piece for CricXtasy, the perfect hypothetical pacer must run in at 7 m/s (or in layman’s terms, the ideal speed to maintain the ideal amount of momentum Watson was talking about).

For this, Hasan can work with a sports biomechanist such as Ferdinands, and/or of course, a fast bowling coach.

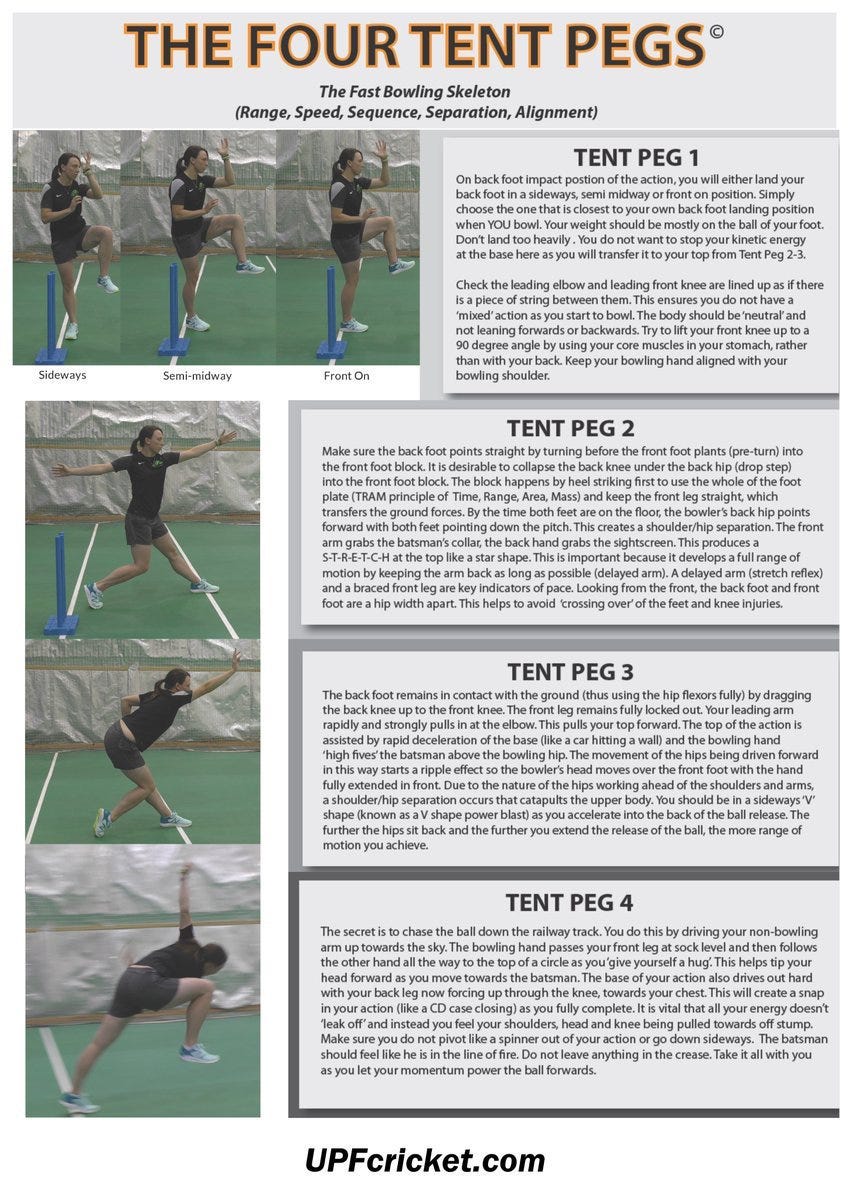

Speaking of, renowned fast bowling coach Ian Pont created a “Fast Bowling Skeleton” image demo with four tent pegs.

In Tent Peg 4 (follow through), it states that “it is vital that all your energy doesn’t 'leak off’ and instead you feel your shoulders, head and knee being pulled towards off stump.”, and that to “let your momentum power the ball forwards.”

In Hasan’s Tent Peg 4, he is found to be running down the pitch whether it is a left or right handed batsman, indicating he needs to improve his use of base of the action.

In Exhibit E, his jump and gather are shortened, resulting in an inability to fully complete his action (shown by how far his non-bowling arm travels) and hence not getting full momentum behind the ball.

This can be countered by further extending his non-bowling arm’s distance in the follow-through through lengthening his jump and gather.

Another thing I would like to shed light on specifically is Hasan’s death bowling in the T20 World Cup.

To contrast, Hasan took 4 wickets at an average of 17 odd with an economy rate of 8.68 in 7.5 overs at the death (overs 17-20) in the Abu Dhabi leg of PSL6. In the T20 World Cup, the death stats significantly dwindled down to stats not even a spinner bowling at the death would be proud of: 1 wicket (that being the aforementioned Jadeja scalp) at an average of 65 odd with an economy rate of 13.00 in 5 overs. I personally feel that taking into account the South Africa warm-up match, these stats are not entirely surprising. For the unbeknownst, warm-up matches do not count towards T20/T20I stats.

In that fixture, Hasan was given the final over, having to defend 19 runs against a well-set Rassie van der Dussen (who is a pace hitter) and David Miller, another well-renowned pace hitter.

First ball, Hasan bowled a full toss that was clubbed away for six by van der Dussen. Next ball, Hasan went short and only conceded a run. The third ball, Hasan attempted a yorker but failed, which led to him being punished for a six by Miller. Fourth ball, Hasan nailed the notes and got it right in the blockhole; one run.

Penultimate ball, Hasan went for the wide yorker but went for four. Final ball, with 1 needed off the final delivery and scores level, a bowler goes one of two paths: stick to their strength or go for the high-risk high reward length in the yorker.

Hasan had attempted three yorkers leading up to the final ball and successfully attempted two yorkers, conceding five runs. For the lone failure (the full toss), it went for six, emphasizing how volatile the yorker length is.

With a 66% percent success rate in the over so far, Hasan chose to attempt another yorker in the final delivery but failed, and conceded the final blow that lost Pakistan the game, bringing his eventual yorker success rate for the over down to 50%.

Leading to their clash against Pakistan, Matthew Wade had a career strike rate of 134.2 against right-arm medium bowling at the death in T20Is, his second-best strike to right-arm fast bowling.

Hasan conceded a six and a four in the 18th over to Wade, with the six coming off a length delivery and the four off a full length. The over brought the requirement down to 22 off 12 deliveries from 37 off 18 deliveries.

Shaun Pollock (who played T20 cricket during its early years and served as Mumbai Indians'mentor-cum bowling coach from 2009 to 2013), will tell you that to succeed at the death, you must bowl yorkers and do your homework on the opposition.

Lord’s Cricket Ground also classifies a death bowling masterclass as one filled with yorkers, but being able to successfully nail the 1-3 meter length consistently is another case of easier said than done.

Committing successfully attempting the yorker to muscle memory is like perfecting Gordon Ramsay’s Beef Wellington recipe, specifically tightening down the Parma Ham, Mushroom Duxelle, seared Filet Mignon brushed with English Mustard in a layer of plastic extremely tightly to ensure everything stays together when you bake it in the puff pastry. In layman’s terms, it’s pretty damn difficult to successfully attempt the yorker with pinpoint accuracy constantly.

However, doing your homework on the opposition is a significantly more tranquil procedure than the former, finding out the strengths and weaknesses of the batsmen and using it to your advantage. And of course, the homework isn’t just restricted to the death overs, it is a principle for all three phases of T20 cricket.

For instance, West Indies’ Nicholas Pooran is known to be virtually a sitting duck against 140+ pace and the short ball. England, whose limited overs team is very well regarded for their analytical approach to the game, reaped maximum earnings of Pooran’s weakness against 140+ pace in the second match of the T20 World Cup.

In the 9th over of the first innings, Tymal Mills conceded no runs against Pooran in the four legal deliveries he bowled to him, all 140+ pace, before Pooran was eventually foxed by a 143kph delivery in the penultimate ball of the over.

For a death overs specific example, West Indies limited-overs skipper Kieron Pollard, whose entry point is typically during/towards the death, is also weak against short balls and 140+ pace, so a 140+ pacer whose role is that of an enforcer may be brought on to harass Pollard with a barrage of short/short of a length deliveries before he is set.

Now what’s the point of the two aforementioned examples you might ask?

Pakistan was undoubtedly the personification of perfection for 99.9% of their T20 World Cup campaign. The 0.1% margin of error would be bowling Hasan to Wade at such a crunch circumstance, given not only Wade’s prior record against right-arm medium bowling, but also the overall record Hasan cultivated during the T20 World Cup. Bowling Hasan to Wade in my opinion screams Pakistan management forgot to complete their homework, for you could be dominating in all 239 balls of a T20 match, but that one ball you don’t dominate can very well be equivalent to that of a magnitude 10 earthquake, whilst those 239 balls could end up being a mere magnitude one earthquake. Pakistan essentially asserted that level of dominance leading to the 18th over of the second innings.

Another factor that can also aid Hasan is simply playing under a progressive management like he does in the PSL for United. Doing your homework on the opposition will not only make Mickey Arthur proud (hence the emphasis in this article), but also emanate results like the aforementioned Mills-Pooran showdown.

Another thing worth diving into is the vast differences between Hasan’s current PSL franchise, Islamabad United and the Pakistan management.

The brains of United management, Hasan Cheema and Rehan-ul-Haq are well known within the Pakistan cricket community for their analytical approach to the game like that of England’s, in a culture where many celebrated figures to have played for Pakistan (and hence usually a strong influence in the internal matters of Pakistan cricket) basically spit on stats and analytics like how a rich English snob might spit on the poor.

The duo’s approach to the game saw them bring the best out of Asif Ali consistently in the PSL, which led to him being slapped the tag of “PSL bully” by Pakistani fans (including myself admittedly), as he was unable to translate his PSL success to the international level for the majority of his international career so far.

However, if that Pakistani fan becomes a seasoned fan (or an unbiased fan at that), he will eventually figure out how progressive the United management is compared to the stone-aged mindset of the Pakistani management, who grasp on intangible straws such as “passion, aggression, and vibes.”

All in all, if a man can acknowledge the adversity in the path before him and still struggle toward the light, then his spirit cannot be broken. Perhaps all the spirit needs is fluid control of run-up speed itself.